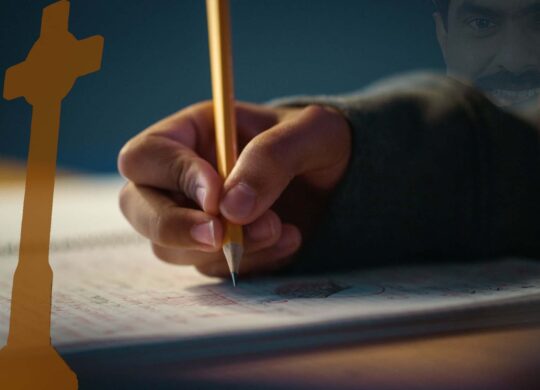

Hands!

They say the human hand is a marvel of nature. No other creature on earth, not even our closest primate relatives, has hands structured quite like ours, capable of such precise grasping and manipulation.

But there’s not a whole lot of precise grasping and manipulation going on with our hands these days. It’s all mostly tapping screens, swiping phones, thumbing alphabets, and pushing buttons. And, said The New York Times the other day, some experts believe our shift away from more complex hand activities could have consequences for how we think and feel.

Dr. Kelly Lambert, a professor of behavioral neuroscience at the University of Richmond in Virginia:

When you look at the brain’s real estate—how it’s divided up, and where its resources are invested—a huge portion of it is devoted to movement, and especially to voluntary movement of the hands. I believe working with our hands might be uniquely gratifying.”

Lambert and her colleagues found that rats that used their paws to dig up food had healthier stress hormone profiles and were better at problem solving compared with rats that were given food without having to dig (“Influence of Effort-Based Reward Training on Neuroadaptive –Cognitive Responses,” in Neuroscience). Even coloring (“Sharpen Your Pencils: Preliminary Evidence that Adult Coloring Reduces Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety,” in Creativity Research Journal) has been shown to have cognitive and emotional benefits, including improvements in memory and attention, as well as reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms. Hands-on tasks that fully engage our attention—and even mildly challenge us—can support learning.

In fact, earlier this year, researchers from Norway declared that “Handwriting but not Typewriting Leads to Widespread Brain Connectivity,” in Frontiers in Psychology.

Said Dr. Audrey van der Meer, one of the authors of that study and professor of psychology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim:

With handwriting, you have to form these intricate letters by making finely controlled hand and finger movements. Each letter is different, and requires a different hand action. The act of forming a letter activates distinctive memories and brain pathways tied to what that letter represents (such as the sound it makes and the words that include it). But when you type, every letter is produced by the same very simple finger movement, and as a result you use your whole brain much less than when writing by hand.”

Now we know why God handwrote!

“Yahweh gave me [Moses] the two tablets of stone written by the finger of God—and on them all the words which Yahweh had spoken.”

Deuteronomy 9:10

And Jesus:

Jesus stooped down and with His finger wrote on the ground.

John 8:6

Dr. van der Meer continued:

Skills involving fine motor control of the hands are excellent training and superstimulation for the brain. The brain is like a muscle, and if we continue to take away these complex movements from our daily lives—especially fine motor movements—I think that muscle will weaken.

That’s why God’s brain is so great and mine isn’t. I can’t remember the last time I handwrote anything, even prescriptions. And every one of those 500,000 words of my most recent commentaries on the Psalms was typed. Woe is me!

Dr. Lambert concluded:

You know, we evolved in a three-dimensional world, and we evolved to interact with that world through our hands. I think there are a lot of reasons why working with our hands may be prosperous for our brains.”

Maybe. Does making a PBJ count? I need another.

SOURCE:The New York Times

Abe Kuruvilla is the Carl E. Bates Professor of Christian Preaching at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Louisville, KY), and a dermatologist in private practice. His passion is to explore, explain, and exemplify preaching.

Abe Kuruvilla is the Carl E. Bates Professor of Christian Preaching at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Louisville, KY), and a dermatologist in private practice. His passion is to explore, explain, and exemplify preaching.